| / Documentaries / Philosophy, Religion |

Introduction to Advaita Vedanta

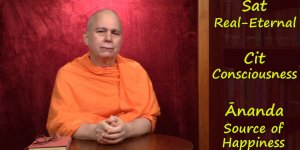

Part 1/6: Discovering the True Source of Happiness

A video presentation by Swami Tadatmananda Saraswati, Arsha Bodha Center, United States

(Tapescript) Welcome! In this series of videos, I’d like to share with you some insights about the teachings of Advaita Vedanta.

These presentations will introduce various topics in a sequence that follows the methodology used by most traditional teachers. These presentations will also show how Vedantic teachings are to be incorporated into your own process of spiritual growth.

First of all, let’s briefly define the word, Vedanta. This sanskrit word literally means the final part or anta of each of the four Vedas. The first parts of the Vedas are dedicated mostly to prayers and rituals, whereas the last part is focused on the spiritual wisdom of the ancient rishis. The particular texts that form this last part are called upanishads.

So, Vedanta consists of the wisdom of the ancient rishis as found in the upanishads, and in other scriptures based on the upanishads, like the Bhagavad Gita.

From the standpoint of spiritual practice, Vedanta is understood to be moksha shastra, which means scriptural teachings that lead to liberation, moksha.

Moksha literally means freedom, but not merely freedom from rebirth, as some people think. Moksha also means freedom from suffering, here and now. An enlightened or liberated person is one who’s been completely freed from suffering through the teachings of Vedanta.

Simply speaking, Vedanta is a solution to the problem of human suffering.

But then, is it even possible to be completely free from suffering?

Everyone experiences physical and emotional pain. Is moksha like an anesthetic that somehow numbs our bodies and deadens our emotions to eliminate any kind of pain?

Huh. That wouldn’t be desirable at all. In fact, pain calls our attention to problems that need our attention. It’s kind of a warning system. In the absence of pain, serious physical and emotional problems could go unaddressed.

But, there’s a difference between pain and suffering. When you feel pain, you also react or respond to that pain. When you have a splitting headache, you might think, “When will this awful throbbing stop?”

Or, when a loved one dies and you feel deep sadness and loss, you might respond to such painful feelings by thinking, “How can I go on living without him? My life will never be the same.”

These anguished responses and tormented feelings are examples of suffering, the suffering that arises as a reaction to physical or emotional pain.

To be clear, pain is a basic physical or emotional feeling, but suffering, on the other hand, is the distress or anguish that arises in response to pain.

When we experience pain, however bad it might be, the feeling of suffering that accompanies it will makes us feel even more miserable.

For human beings, pain is inevitable. But fortunately, suffering can be avoided. It’s possible to experience pain without suffering. That is, you can feel physical or emotional pain without all the distress or anguish that usually accompanies it. This isn’t as improbable as it might seem.

You, yourself, experience this when you watch a sad movie. Even though it’s just a movie, the sadness you feel is real sadness, and your tears are real tears. But, when you cry during a movie, you don’t experience the distress or anguish of suffering.

If a character tragically dies in a heartbreaking scene, you'll feel really sad, but you won’t think, “Why did this have to happen to me? Why me?” You don’t suffer during the movie, because nothing truly happens to you. You’re absolutely ok in spite of the tragic death. In fact, you actually enjoy the sadness you feel during a movie.

So, if you can enjoy movie-theater-sadness, do you think it might be possible to experience real-life-sadness without any suffering?

It might be possible, but only if physical and emotional pain doesn’t truly affect you. And that is exactly what the ancient rishis discovered - that the truth or essence of who you are is utterly unaffected by pain. They used the word atma to designate what is sometimes called “the inner divinity,” or “your divine nature,” or “the presence of God within you.”

According to the rishis, atma, your essential nature, is full, perfect, complete. It’s the true, inner source of happiness.

However, this inner reality is usually well-hidden. It’s concealed or covered by a dark veil of ignorance. That inner reality, then, remains unknown, unrecognized, unrealized.

But, that inner reality is actually the truth of yourself, so how can you remain unknown?

There’s a problem here, a problem that we can call self-nonrecognition. Self-nonrecognition means the failure to know your true nature to be full, complete, and the source of happiness.

Self-nonrecognition is a fancy term that simply means ignorance of your true self, atma. This veil of ignorance conceals the divine reality hidden within you, so it must be removed. Ignorance, of course, is removed by knowledge. And ignorance in the form of self-nonrecognition is removed by knowledge of the true self, atma.

This self-knowledge, or atma vidya, can be gained through the teachings of Vedanta. These teachings lead you step by step to discover what the ancient rishis discovered.

The discovery of your true nature is called liberation or moksha, because it results in complete freedom from suffering. You yourself can be free from suffering when you discover that your essential nature is utterly untouched by pain, and that you are ok, no matter what.

Now, we all want to be free from suffering. We all share that desire. Desire, or kama, is a basic, universal feeling. We desire whatever it is that can remove suffering and produce happiness.

In fact, desire seems to drive everything we do. Think about it. Going to work, what you do at home, your time with friends and relatives - all this, in one way or another, is driven by your desire to avoid suffering and enjoy happiness. Desire ultimately provides the stimulus or motivation for all our actions.

It’s true that your desires are likely to be different from the desires others have, but, all these desires have something in common. That is, when our desires remain unfulfilled, we suffer. We feel deficient or incomplete. We feel that something is missing.

But by fulfilling desires, we seek to remove that feeling of being deficient or incomplete. In other words, by fulfilling our desires, we seek fullness, completeness, and contentment.

OK, now we’re ready for one of the most important questions in this inquiry, a question about the actual source of the happiness and contentment we seek through fulfilling our desires.

Is it true that the fulfillment of a desire itself produces happiness and contentment? At first, this might sound reasonable, but on examination, it’s easy to spot a problem.

When you see a cute baby smiling sweetly, or when you watch a beautiful, golden sunset, you'll probably feel happy and content at least for a few moments. But, what desire did you fulfill by seeing that smiling baby or beautiful sunset?

Now you can see; without fulfilling any particular desire, you CAN feel happy and content. So, we have to conclude that fulfilling desires is not the actual source of happiness and contentment.

Then, what is the actual source of happiness and contentment?

The answer to this question is found in a universal truth that you already know: the true source of happiness lies within you. The same truth was expressed by the ancient rishis. And even though many people understand this intuitively, it’s really important to know how and why it’s true.

Here’s an anecdote that will help. Long ago, when I was teaching a group of schoolchildren, I asked them, “What is the source of happiness?”

One boy replied, “Chocolate ice cream.”

"OK," I said, "if a scoop of ice cream is the source of happiness, what would you say about two scoops?"

The boy said, "That would make me twice as happy."

So I asked, "what about three scoops?", and he answered, "I’d be three times as happy."

Then I said, "suppose you ate the entire 5-gallon container of ice cream from which all those scoops were served."

His eyes grew wide and he said, “That would be totally awesome!”

Of course, he’d be totally sick before eating even a part of that. But, if ice cream truly were the source of happiness, then he should indeed find it “totally awesome”.

This little story shows us something we already know about eating ice cream. Happiness is not an ingredient in the ice cream, along with the milk, sugar, and chocolate. So, because any happiness you feel can’t come from the ice cream, it can only come from within you.

Here’s a Vedantic explanation about how ice cream makes you feel happy. Eating it fulfills your desire for ice cream, but you continue to have many other desires that remain unfulfilled. You’ll still want a better job, a new car, a nice vacation, etcetera. And, these unfulfilled desires usually make you feel deficient and incomplete, as we discussed before. But, while you’re enjoying the ice cream, those feelings of incompleteness are temporarily driven away by the pleasure of eating the ice cream. And, in the absence of feelings of incompleteness, happiness naturally and spontaneously arises within you. Even though happiness is always present within, feelings of incompleteness obstruct your experience of it.

Like when clouds cover the sun, it continues to shine, but you don’t experience its warmth and brilliance. Then, when the clouds go away, you experience the sun fully.

In the same way, the true source of happiness always shines within you, but it’s often covered up, so to speak, by feelings of incompleteness. When a pleasurable experience dispels those feelings of incompleteness, the ever-present happiness within you shines forth. That means, contrary to what you might think, happiness is not something you get. Instead, it arises naturally and spontaneously when you get rid of something; when you get rid of your feelings of incompleteness and the desires associated with them.

Even though many people intuitively understand that the true source of happiness is within, their day to day behavior doesn’t seem to reflect this understanding at all. For example, how many hours a day do you spend seeking happiness at its true source within, and how much time do you spend seeking happiness outside of yourself, even though you know the true source of happiness is within?

Obviously, there’s some confusion here. We’ve already discussed the cause for this confusion, which is the veil of ignorance that conceals your true, divine nature. This ignorance prevents you from recognizing your innate fullness and completeness. And that’s why we call it self-nonrecognition. As a result of this self-nonrecognition, you’ll naturally feel deficient and incomplete. And when you feel deficient and incomplete, you’ll certainly be driven by desire to seek out those things and experiences that can make you feel less deficient and more complete. Simply put, you seek happiness and contentment.

The problem is, as long as you’re driven to seek out happiness and contentment outside of yourself, your search will go on endlessly. You’ll never find lasting happiness and contentment, because you’re actually looking in the wrong place. Self-nonrecognition leads to a life of endless seeking. This search is punctuated by moments of happiness, no doubt, but it never culminates in finding perfect peace and uninterrupted contentment.

There’s a delightful story that’s often used to illustrate the problem of self-nonrecognition. It’s called the tenth man story, even though it usually refers to 10 boys.

These boys were brahmacharies, religious students, who lived and studied with their guru in a traditional school, a gurukulam. When a particular religious festival was approaching, the guru instructed his 10 young disciples to go on a pilgrimage to a special temple for the celebrations. The guru himself was too old to make the journey, which required several days of travel on foot - over fields, through forests, and across rivers.

When the boys were enroute, one of the rivers they had to cross was too deep to wade across and no ferry boat was available. So, one by one, they each swam across the river. Then, they wanted to be sure that everyone got across safely, so one of the boys counted the others.

Looking around, he counted, 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, but he neglected to count himself.

He said, “Where’s the 10th boy?”

Another boy thought there was a mistake in that tally, so he counted, 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9...

Huh. He also neglected to count himself.

Eventually, each of the boys counted the others, and each neglected to count himself.

They were soon stricken with fear, thinking that one of their classmates had gone missing. Then they began to run about frantically, looking for the missing boy. They looked upstream and downstream, in the fields and forests on both sides of the river, but they couldn’t find their missing classmate.

Before we continue with the story, you can see how nicely it illustrates the problem of self-nonrecognition. Each of the boys failed to count himself. And as a result, each of them was actually searching for himself. In a similar way, WE fail to recognize our own true natures as being full and complete. We fail to recognize the true source of happiness present within. And as a result, we end up searching for happiness outside of ourselves, looking for the happiness that actually lies within.

The boys’ frantic search was doomed to failure, because they were all looking in the wrong place. In the same way, our search for happiness outside of ourselves is also doomed to failure, because we, too, are looking in the wrong place. In spite of that, it wouldn’t be so bad if our search for happiness was pleasant and enjoyable, like the game of hide and seek that children play. But, our search for happiness is often not much fun.

The boys were miserable while searching in the fields and forests. They felt terrible anxiety and they were eventually exhausted by their frenzied efforts.

In the same way, our search for happiness in the world is often fraught with great anxiety and frustration. We face a variety of obstacles, we struggle to overcome a great number of difficulties, and we may eventually find ourselves exhausted by all this effort.

Let’s return to the story.

After several hours of panic-stricken searching, the boys gathered together and started to weep. They had come to the conclusion that their classmate had drowned in the river and was swept away by the current.

A passerby happened to see this group of brahmacharies sobbing on the riverbank. He asked what had happened, and as they narrated their tragic story, he could easily see that all 10 boys were standing there. He was able to surmise that each of them had failed to count himself. So, he told the boys that their classmate was indeed alive, and, that he was standing amongst them right now.

Each of the boys looked around for their missing classmate, and were deeply disappointed not to find him. They wondered if the passerby was playing a cruel joke on them. The problem was, they were still looking in the wrong place. Even though the passerby told them the truth, that wasn’t enough. Something more was required to dispel their ignorance.

In the same way, when we are first exposed to the teachings of Vedanta, we soon learn the great truth revealed by the rishis - that our true nature is divine, full and complete. Yet, like the ten boys, we too don’t really get it at first. Even though we understand the words of the rishis, it’s not enough. Something more is required.

What’s missing? The last part of the story will make it clear.

One of the boys said, “How could our missing classmate be here right now?”

The passerby took him aside and asked him to count once again.

The boy counted 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9.

And then the passerby said, “You counted 9, but you didn’t count yourself. You are the tenth.”

Then, the boys immediately realized that each of them had failed to count himself. And, they were immensely relieved to know that no one had actually drowned.

This story not only illustrates the problem of self-nonrecognition, it also demonstrates a basic principle of teaching, a principle based on the difference between telling and showing. Merely telling students about something is not enough. Students must be shown. They must be led to personally discover what the teacher wants them to understand. Therefore, the methodology used in teaching is just as important as the material being taught. Without an effective teaching methodology, students will never understand. And this is most certainly true of Vedanta.

What makes Vedanta unique is not WHAT it teaches, but rather HOW it teaches. Other spiritual traditions also profess that your true nature is divine, full and complete. But what distinguishes Vedanta, is its powerful and meticulous teaching methodology. At the heart of this methodology is a practice called atma-vichara or self-inquiry. So, Vedanta doesn’t merely tell you that your true nature is full and complete.

Instead, it uses it’s unique methods to lead you, step by step, by means of an inward-turned process of self-inquiry, atma-vichara, which culminates in the discovery of what the ancient rishis discovered - discovery of your innate fullness and completeness which is the true source of happiness.

That very process of self-inquiry will form the basis for our next discussion.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE