| / Documentaries / Philosophy, Religion |

Introduction to Advaita Vedanta

Part 2/6: Atma - Sat Cit Ananda

A video presentation by Swami Tadatmananda Saraswati, Arsha Bodha Center, United States

(Tapescript) Welcome! In the prior presentation, we discussed how the ancient rishis discovered the divinity hidden within us all, the inner reality they called atma, the true self, ever full and complete, the true source of happiness.

But, this reality is usually concealed by a veil of ignorance, so we fail to recognize our innate fullness and completeness. We called this "the problem of self-nonrecognition".

As a result of self-nonrecognition, we naturally desire and seek out things and experiences in the world that can make us feel more full and complete. Unfortunately, this search for worldly happiness turns out to be badly misdirected, because the true source of happiness is actually within us.

In this presentation, we’ll explore the nature of that inner source of happiness - your true self, atma.

Many scriptures describe atma with the words sat cit and ananda.

Sat means that which is real or true, that which exists unconditionally. To exist unconditionally is to be timeless, eternal, unborn, uncreated.

Atma is indeed unborn, existing eternally before your present birth.

Cit means the consciousness or awareness because of which you are sentient being. Unlike insentient things like rocks and clouds, you have the power to know, to feel, to experience things.

These two words, sat and cit, put together, help us understand that atma is an eternal conscious being, unborn, uncreated and sentient.

And, that conscious being is you. There is no other atma. Whenever you say “I” using the first-person pronoun, you’re ultimately referring to atma.

Atma is not a third-person he, she, or it. Atma is not a this or that. Atma is the core or essence of who you are.

Now we come to the third word used to describe atma, ananda. Ananda is often translated as bliss, but that’s a really poor translation; and here’s why. If you say, "I experienced bliss yesterday," this statement shows that bliss is something you can experience, like happiness or sadness. But, we’re talking about the conscious being who experiences things like bliss, happiness and sadness. Bliss is what you experience; it’s not who you are. So, it’s better to understand the word ananda as indicating the inner source of happiness, the true source of fullness and contentment within you.

Then, when we put all three words together, sat cit ananda simply means that atma is an eternal conscious being which is the true source of happiness.

When we use the words consciousness and awareness in Vedanta, they have a very specific meaning that’s quite different from what’s used elsewhere. Doctors use the word consciousness to describe a patient’s ability to respond to external stimulation. When doctors say a patient is conscious, it means he can respond to you. Obviously, that’s not how we use the word consciousness in Vedanta.

Other people use the word consciousness to mean alertness or attentiveness. Attentiveness is the mind’s ability to be focused on something. When someone refers to “body consciousness” or “environmental awareness,” they’re actually talking about focusing your attention on the body or on the environment. In the same way, the phrase, “making a conscious decision” means focusing your attention on decision making. Now, attention or attentiveness is a quality of the mind.

But, in Vedanta, consciousness is not a quality of the mind, it’s the one who knows of the mind. Consciousness is the sentiency because of which the qualities and activities of the mind are known. Whatever happens in your mind is known to you because of consciousness.

Just as light reveals objects in a dark room, the light of consciousness reveals mental objects in your mind. You can know, feel, and experience things because of consciousness, because you are a conscious being.

Now, there’s a subtle point here that’s really important to understand. Strictly speaking, consciousness is not something you have or possess; consciousness is who you are. You can own a car and possess a body, but you can’t possess consciousness.

Why?

A possession is something you can lose, and in its absence, you still exist. If your car is stolen, you still exist. While you’re sleeping or in a coma, your body is gone, in a manner of speaking, yet, you still exist. So, you can possess a car or a body, but you can’t possess consciousness, because you would cease to exist without it. Consciousness is your essential nature; it’s not something you own.

Therefore, you don’t HAVE consciousness; you ARE consciousness. This might be the most important point in this entire presentation, so let me say it again: you don’t possess consciousness; you ARE consciousness. If you get this wrong, everything that follows won’t make any sense.

Then, how do you know that you are conscious being? Well, if you weren’t, you couldn’t be watching this presentation right now. You don’t need Vedanta to know that you’re conscious. Your nature as a conscious being is said to be self-revealing or self-evident. You know the world around you by means of your five senses, but you know your consciousness directly, without your senses.

To understand this better, suppose you’re in a dark room, using a flashlight to reveal whatever’s inside the room. Like that, you use your five senses - sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch, to reveal objects in the world.

On the other hand, you don’t need a flashlight to see the sun shining brightly outside. The sun is self-shining or self-revealing. And so too is consciousness. This self-shining consciousness reveals all that you experience. Every object or person in the world you have ever encountered was known to you because of that consciousness. And every thought, emotion or feeling that has ever arisen within you became known to you because of that same consciousness.

Now, consider this: consciousness is present in every experience we have. And because it’s always present, we naturally take it for granted. We think that consciousness is something quite ordinary.

But, the ancient rishis discovered that it’s actually quite extraordinary. They extolled consciousness as being divine and they said it was unbounded, limitless, infinitely vast.

Then, how is it that the same self-evident consciousness that the rishis deemed extraordinary is understood conversely by us to be ordinary? The reason is this: even though consciousness is self-evident, it’s full, complete nature is not self-evident. Its extraordinary qualities are concealed by a veil of ignorance, as we discussed before.

The veil of ignorance, so to speak, is not totally opaque, it’s somewhat transparent, like thin, sheer fabric. If an object were covered by this kind of fabric, you’d know that something is there, but you wouldn’t know exactly what it is.

The famous Vedantic example about the rope-snake shows this nicely. In a dark alley where a length of rope lays curled on the ground, you might imagine seeing a poisonous snake. If the rope was totally obscured by darkness, you wouldn’t see a snake, you wouldn’t see anything. But when the rope is partially obscured by darkness, you can’t see its details and therefore you can imagine it being a snake. This example shows how the veil of ignorance partially obscures your true nature.

Ignorance allows you to know that you are conscious, but it doesn’t allow you to know the extraordinary nature of that consciousness. Ignorance has the power to partially obscure anything we experience. And because of this, ignorance can lead us to misinterpret our experiences.

In fact, we misinterpret our experiences all the time. The rope in the dark alley is mistaken to be a poisonous snake. The atmosphere is colorless, yet we say "the sky is blue". Or, to use my favorite example, every time we watch a beautiful sunset, we say, the sun is going down. But as a matter of fact, the sun doesn’t go down. We know very well that the sun doesn’t travel around the earth; it actually remains stationary in the sky while the earth rotates on its axis.

If we could see it from above, it would look like this. Because of the earth’s rotation, we’re actually tilting over backwards when we watch the sunset. And that makes the sun look like it’s going down. But the truth is, the sun doesn’t move; it’s we who are moving.

This example vividly shows the power of ignorance to make us misinterpret our experiences.

Since it’s so easy to misinterpret experience, do you think it’s possible that we might misinterpret our experience of ourselves as conscious beings?

That’s exactly what happens.

This problem of misinterpretation can be best explored by using one of the most fundamental and important teaching methodologies found in Vedanta. The method is called drik drishya viveka, which means separating or distinguishing the seer from the seen. The words seer and seen are used figuratively here to indicate the knower and the known.

The entire world, all that exists, falls into one of these two categories: seer or seen, knower or known. The difference is easy to discern.

You, as a conscious being, are the seer, the knower; you are the one who knows the existence of everything and anything that can be known. You are the knowing subject, and everything else consists of various objects known to you, from tiny speck of dust to the great Himalaya mountains.

Now, whatever is known to you as an object is necessarily different or separate from you, the knower. For example, this table is known to me, therefore it’s different from me. This cloth is known to me, so it’s separate from me. OK, then what about my body.

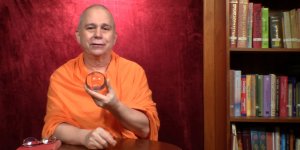

This body is an object known to me in the same way that this cloth is known to me. So, this body must necessarily be different from me, the knower of the body. Consider the fact that the hardness of the table belongs to the table, and not to me. In the same way, the orangeness of this cloth belongs to the cloth, and not to me. But, when it comes to my body, things get really confusing.

This happens to be a male body. And the maleness of this body should belong only to the body, and not to me. Then, why is it that I can say "I am male"? If my cloth is orange, I can’t say, "I am orange".

Even though this cloth and this body are both mine, I have a different relationship with each of them. I possess this body, like I possess this cloth, but my body seems to be more than just a mere possession.

What makes my body different?

Unlike the cloth, my body is pervaded by the sense of touch. I feel sensations throughout my body, but I don’t feel anything when the cloth is touched. We have no sensations in our hair and nails; that’s why we can cut them. But, we’re not prepared to cut our arms and fingers, because of the presence of sensation.

Even so, from a Vedantic perspective, it’s a big mistake to consider this body to be different from the table or cloth, merely because it has some sensations. We can show how this is the case with several examples.

Suppose I took a medication which had the strange side effect of making my nerves grow right through my skin, and into this cloth I’m wearing. Then, touching this cloth would feel the same as touching my skin, and I would consider the cloth to be like any other part of my body, just because of the presence of sensation. Besides that, before taking the medication, based on the color of my skin, I could say, "I am white". But after taking the medication, based on the color of this cloth, which feels like part of my body, I would say, I am orange. But that’s absurd. These examples show how my body seems different from the table and cloth merely due to its sense of touch.

So, what would happen if this body were to lose its sense of touch? What happens when part of YOUR body is numb, like after a dentist appointment, when anesthetic has been used. Your lip might feel like a foreign object stuck onto your face somehow. Or, if you fall asleep laying on your arm and wake up with it completely numb, you might wonder, "whose arm is that?" So, if your entire body were numb, from head to toe, what would that be like?

Huh. You’d feel no more connected to your body than you would to a table or piece of cloth.

Think about it. The presence of sensation makes your body seem like it’s more than a mere possession, but ultimately, it’s just like anything else you own, like a car, for instance. You buy a car, you get inside, and you drive it around for several years, until it’s old and worn out. Then you get rid of your old car and buy a new one.

Your body is not so different. You get a new body at birth, then you inhabit it for a number of years, until it’s old and worn out. Then, when you die, you get rid of your old body and get a new one. So, your body, is not so different from a car or anything else you possess.

If your car is made by the Ford Motor Company, you won’t say, I am a Ford. And if your car is 10 years old, you certainly won’t say, I am 10 years old.

So, how can you define yourself based on the gender and age of your body? Your body is an object known to you, and you are the conscious being who knows your body. As the knower of your body, you are neither male or female, neither young or old. You are simply a conscious being.

All this seems perfectly reasonable, and yet, our confusion persists. We continue to say that we are male or female, young or old, healthy or ill, and so on, in spite of the fact that all these traits actually belong to our bodies, and not to the conscious beings we truly are. All this, of course, is the result of self-nonrecognition.

Suppose you were completely free from this self-nonrecognition. Then, how would you look upon your body? If you truly discovered yourself to be a conscious being, utterly independent of your body, how would that change your perspective?

Let’s explore this. As a result of the practice of atma vichara, self-inquiry, the veil of ignorance that obscures the extraordinary qualities of your true nature will gradually fade away. It’s as if the veil were to grow thinner and thinner, allowing the reality concealed by it to appear with more and more clarity.

As this happens, your relationship with your body will undergo a dramatic transformation. You’ll begin to look upon your body like any other possession. And, knowing that you are simply a conscious being, completely independent of your body, a kind of aloofness or detachment towards your body will arise. Because of this detachment, when the sensation of pain arises in your body, you’ll know that it doesn’t truly affect you, the conscious being, atma. And if that pain doesn’t truly affect you, you won’t go through all the distress and anguish of suffering that you once did. You’ll know that you are absolutely ok in spite of the pain.

This state of detachment towards your body is not to be confused with indifference or apathy.

Detachment is a state of objectivity, a state of clear thinking in which your body is understood to be like any other possession.

Indifference, on the other hand, is a state of complete disinterest and non-involvement. In the presence of indifference, no sense of responsibility can exist. In the presence of apathy, no care or concern can exist.

Yet, we all bear the responsibility to take care of our possessions. If you own a car, you’re responsible for its maintenance. And since you possess a body, you’re responsible for its maintenance as well.

With detachment and objectivity, you can actually maintain your car and your body even better. If your car breaks down on the highway and you start crying, "why me?!" - that’s not going to help get it fixed. And if you’re diagnosed with cancer, and you become deeply depressed as a result, it’s been clinically proven that the outcome of medical treatment is worse when patients are depressed. So, detachment and objectivity can actually help you take better care of your body and other possessions by freeing you from the distress and anxiety that often arise.

Here’s a final observation about caring for possessions.

Suppose your car is being repaired and a friend has loaned you his car for a few days. Will you take care of his car? Of course. Now, whose car would you treat more carefully, your car or his? That’s interesting. If you’re the owner of a car, you might be a bit less concerned than if you’re the caretaker of a car loaned to you. This observation is important because you don’t really own your body.

You can legally own a car or a house, but not a body. In fact, your body is a gift that was given to you on the day of your birth.

Given by whom?

Certainly, you could say it was given by your parents. But you could also say that it was given to you by Ishvara, the god of the cosmos, who bestowed a new body upon you so that you could reap the results of your past karmas.

In either case, your body is a precious gift, and you are the caretaker of that gift. Clearly, there’s no room for any indifference with regard to your body.

As we conclude this presentation, I have to warn you that some of what’s been taught here will be superseded, in a manner of speaking, by later presentations.

Vedanta, as we discussed before, employs a powerful, unique teaching methodology which leads you step by step to discover what the ancient rishis discovered.

If you cross a shallow stream by walking on stepping stones, you have to leave the prior stepping stone in order to move on to the next one. The teachings of Vedanta work in a similar manner. The present step is to understand your body to be a mere possession, like a car.

A future step will require you to give up this idea of possession, and to understand your body to be like any object.

An even later step will be to understand that your body is a physical manifestation of Ishvara.

All these steps will be explored in future presentations.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE